Ohio Bee Survey at Morgan Park

Pollinators, especially bees, may be in distress in Ohio – or maybe they’re doing just fine? Your Portage Park District is part of the ongoing studies to answer that important question. It’s important because most of our foods depend on insect pollination, and bees are the best insect pollinators in the state. Yes, it’s true that corn is wind-pollinated, but who wants to eat a diet solely of corn for the rest of their life? Soy beans and alfalfa are weakly wind-pollinated; their yields are greatly enhanced with bee pollination. Fruits and veggies all need to be bee pollinated, so understanding the status of wild bees in Ohio is important for agricultural purposes, as well as maintaining a rich variety of life for people and other organisms.

The Ohio Bee Survey set out to address this important concern. It is believed that there are about 480 species of wild bees, native to Ohio. But where are they? When can we expect to see them? Which are the most abundant? Or in science-speak: what is the distribution range of wild bees and their phenology? To answer this, 145 observing sites were established in 80 of the 88 counties of Ohio. Morgan Park in Shalersville on SR44 was one of two sites in Portage County; the other site was at the Hiram College Field Station in Garrettsville. The Principal Investigators were Prof. Karen Goodell and Denise Ellsworth, both of The Ohio State University, Dept. Entomology. The project was funded in part by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources for $100,000 per year for three years (Dr. Goodell, PI). The Manitou Fund supported supplies at the beginning of the project (D. Ellsworth, PI) The project was coordinated by MaLisa Spring at the OSU Newark Campus. I was one of over 150 volunteers that helped collect and handle data for this project. Well, technically, I collected bees – the bees were the data. I helped collect, wash, pin, identify and archive the specimens.

Parks are important not only for their recreational benefits; they are also important for research because they are especially protected for the indefinite future. Why Morgan Park? I chose Morgan Park primarily because it’s in the Portage Park District and likely to be around for the foreseeable future and beyond. This study serves as a baseline of the bee community. Ultimately, the plan is to re-visit this study in ten years or so and compare the findings with the findings from 2020. This comparison may show whether pollinator bee populations are in decline.

Procedures

First, I received a Collecting Permit to collect and remove specimens from the site. Bees were collected weekly from May through September 2020, using bee-bowl traps. A bee-bowl trap is a plastic cup, painted blue, yellow, or white and filled with an ounce of water to which is added one drop of unscented dish soap. Thirty bee traps were placed along a transect at 5-meter intervals and left for 24 hours. I chose the transect to study because it was accessible from one of the permanent trails at the park and because it stretched into the field away from foot traffic and possible disturbance. Bees attracted to the colored bowls would land on the surface, expecting to find a flower for nectar or pollen; instead, they would drop through the surface because the dish soap decreased the surface tension of the water. The following day the contents of the bowl were collected on a filter and frozen until transport to OSU at the end of the season.

Once at the lab, the filters were thawed, the contents washed, then the bees were separated from other things caught in the traps (flies, moths, grasshoppers, etc.) and then pinned for identification under a microscope. Each bee was uniquely identified according to its time and date of collection and its GPS position. Identifying bees to species is a VERY tedious and time-consuming process; begun in late 2020, it was completed in October 2023.

Findings

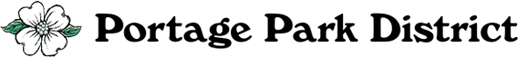

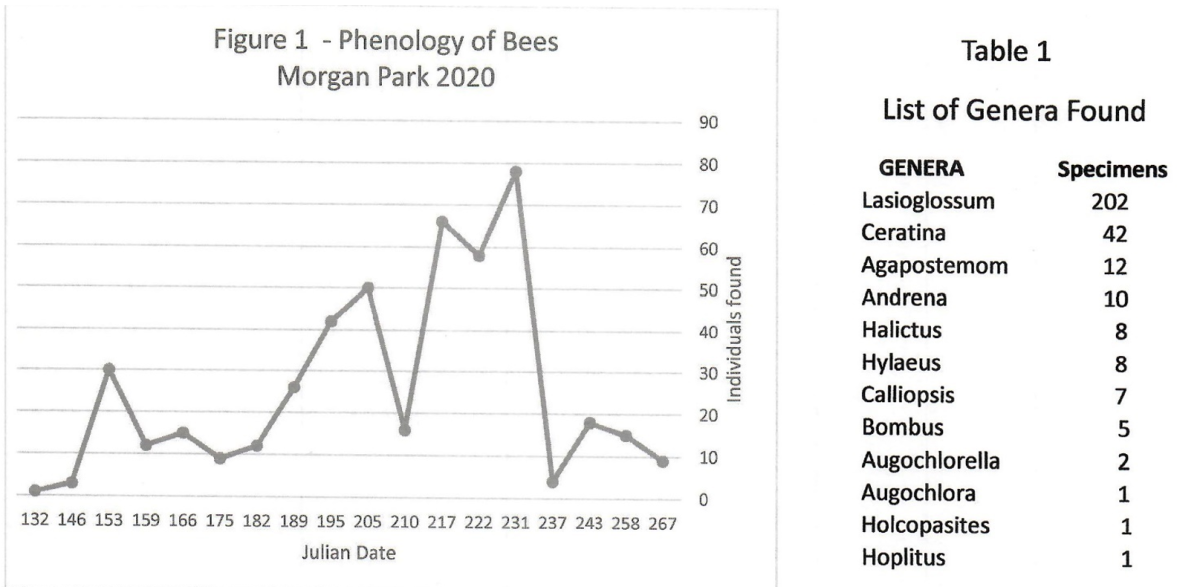

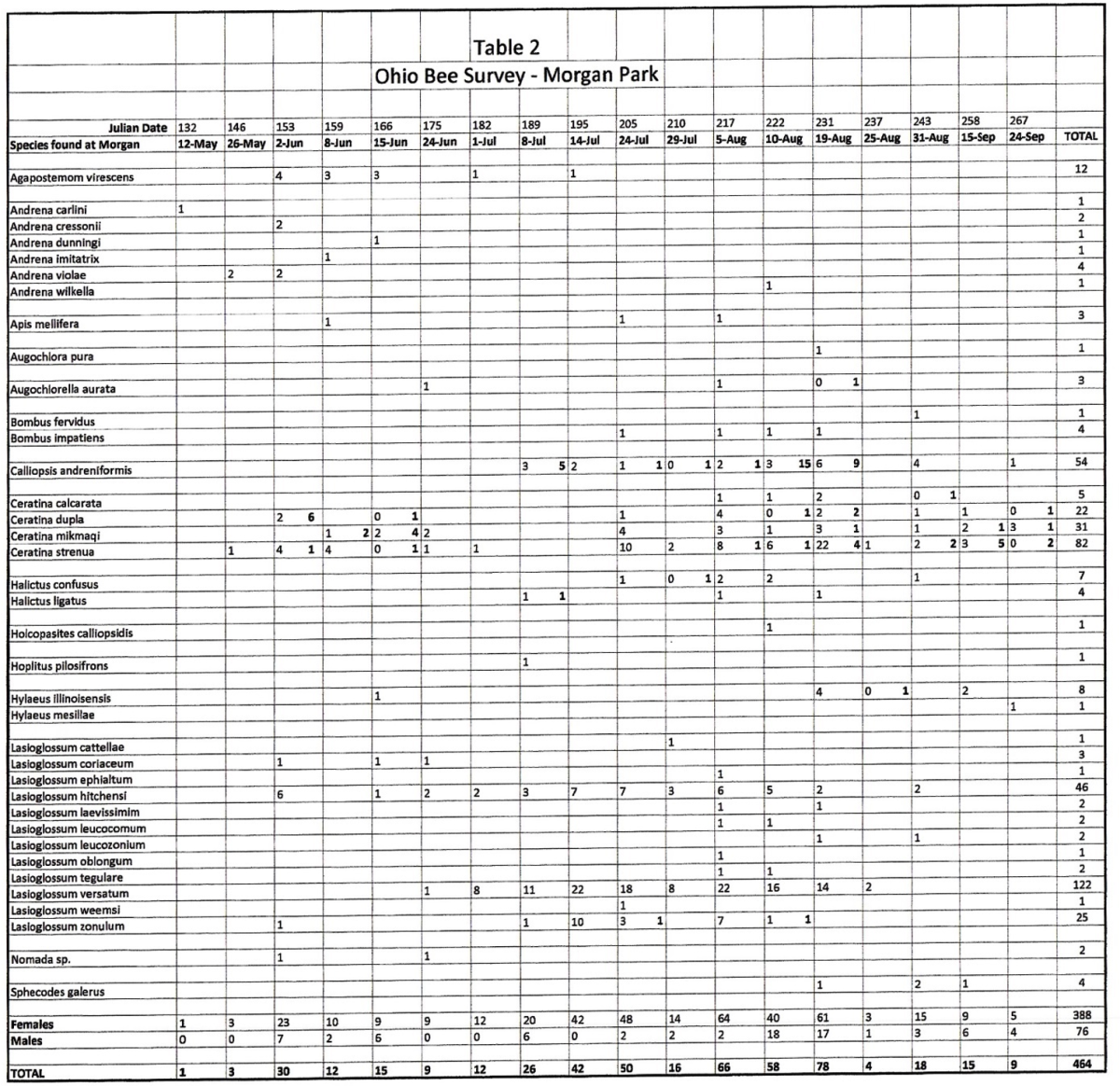

All told, 53,753 bee specimens were collected; 471 specimens were collected from Morgan Park. There were 247 species identified across the state. Some bees were found throughout the state, being collected at virtually all the sites. Seven species constituted over half of all specimens. At the other extreme, some species were found only in the sandy Great Lakes watershed or isolated to other parts of the state. Several species were found at only one site. We identified 36 species of wild bees at Morgan Park, representing five Families, alongside Apis mellifera, the honey bee. Of the wild bee species found at Morgan Park, six were uncommon species, five would be considered rare, and one species (Lasioglossum ephialtum) was found only at Morgan Park. A list of the genera found is in Table 1, along with the number of individuals caught of each genus. The phenology (date of appearance) of each species caught is shown in Table 2. Figure 1 shows the number of bees caught (Y-axis) versus the date of capture (X-axis).

Examining Fig. 1 and Table 2 you can see that bees appeared at three distinct times: Spring time (JD 132 – 175, early May through mid-June), bees such as Andrena, Agapostemon, and Ceratina species dominate. This is followed by the Summer Dearth of mid-to-late June, as spring flowers decline and before summer flowers appear. Summer bees (Caliopsis, and certain species of Lasioglossum dominate) that depend on early summer floral resources, such as sun flowers and milkweeds, (JD: 182 – 210, July through mid-August). Then as asters and goldenrods appear, so too appear the late summer bees that persist into autumn (JD: 217 – 258, August through September); the bee assemblages were dominated by late appearing Ceratina and Hylaeus).

Discussion

Is this a comprehensive list of all the bees we might expect to find at Morgan Park? The short answer is “NO” and for many reasons. All means of catching bees are biased. Nets are biased toward large bees, such as bumble bees, honey bees and large carpenter bees; nets are less efficient at catching small bees. Bee-bowl traps by contrast don’t catch many large bees because large bees can escape the trap, whereas small bees are trapped in greater proportion. For that reason, we only caught two bumble bee species, (Bombus impatiens and B. fervidus) even though I have caught six species of bumble bees and large carpenter bees (Xylocopa virginica) at Morgan Park using a net. Also, there are many environmental variables (light intensity, temperature, cloudiness, time of day, availability of preferred floral resources) that can affect whether a bee will forage. Also, the transect chosen was in the open field, and so would be biased to bees that prefer to forage in open fields, rather than on the edge of a forest or near a water feature. Finally, there are many commonly found bees that didn’t appear in this study but did appear in adjacent counties. All-in-all, it would be reasonable to expect to find at least twice as many species as we found in this effort at Morgan Park.